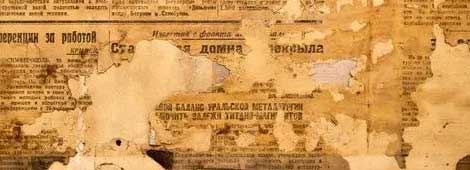

When a conservator considers a single unique paper item for chemical treatment, careful preliminary examination and testing is done to determine to what degree, if any, the paper and/or the design materials on the paper would be changed or damaged by any aspect of the proposed treatment. It is then possible to modify or change the treatment as needed. The process is meticulously controlled and the amount of risk to the item reduced to an acceptable level before proceeding. This very conservative approach, which allows safe decisions to be made for one item or small groups of similar items, is a methodology in which institutions have invested considerable time and money, because it provides a high degree of assurance that original rare and unique holdings will be well preserved. Clearly one of the challenges in approaching mass deacidification is to determine how to proceed in a similarly responsible fashion and be reasonably assured of a positive long-term outcome. Using mass processes to treat books and documents differs from single-item treatment, primarily because mass treatment is inherently more complicated.

First, the number of items to be treated at the same time will be fifty to a thousand times greater. In most research collections, thousands of volumes will have to be treated in a month in order to get the job done in several decades. For instance, if an institution wants to deacidify a collection of two million volumes in twenty years, it will need to treat about 8,300 volumes per month. The ability to exercise careful single-item control will be radically reduced, but the need to exercise a comparable degree of control will still be important to the safety of the collection.

Second, in general, it is not usually economically feasible to do single-item testing prior to mass treating a large collection because of the high numbers of items being treated. Therefore, it will not be possible to detect adverse effects of a process on each item prior to treatment and to adjust for observed problems without incurring much higher costs or reduced production levels. The need for comprehensive test data is still there, but these data will need to be collected before the process is put into use.

Third, the heterogeneous nature of the chemical compounds in most collections greatly increases the possibility of unwanted side effects. Not knowing exactly what inks, dyes, adhesives, binders, or fillers are present in any large batch of items increases the chances of physical or chemical interaction between process chemicals and the chemical materials in the book or document. These effects are unavoidable and should be minimized.

In general, compared to single-item conservation, mass processes will by their very nature lead to higher risks for the books and documents being treated. This risk will always be present and will nearly always be higher than the comparable single-item case, because in mass processes it is impossible to know everything about all the items being treated all of the time. How, then, can mass deacidification be utilized in a responsible way? The answer is, that when evaluating processes, a comprehensive body of scientific and technical information about how mass deacidification actually works in practice is required. Evaluation of this information can lower the risks to the collections during mass treatment and can protect institutions from public liability.